Performance Royalties

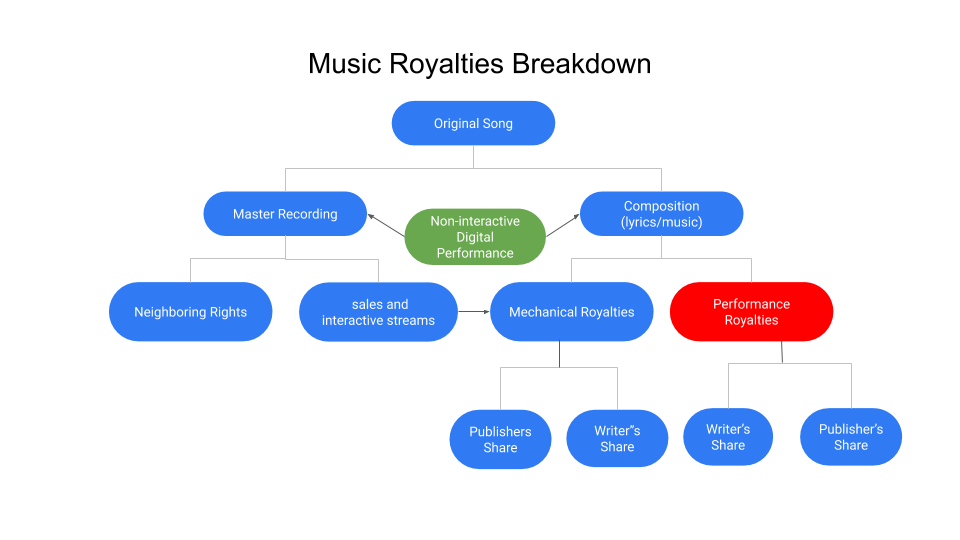

Every song holds two distinct copyrights: songwriters hold the rights to the lyrics and melody of a piece of music, while performing artists/label holds the rights to a particular recording of a song, which is called a master recording. Both songwriters and recording artists typically assign their rights to a third party for management, instead of attempting to track a song’s use and seek payment independently. Song copyrights are typically assigned to music publishers, while master recording copyrights are typically assigned to a record label.

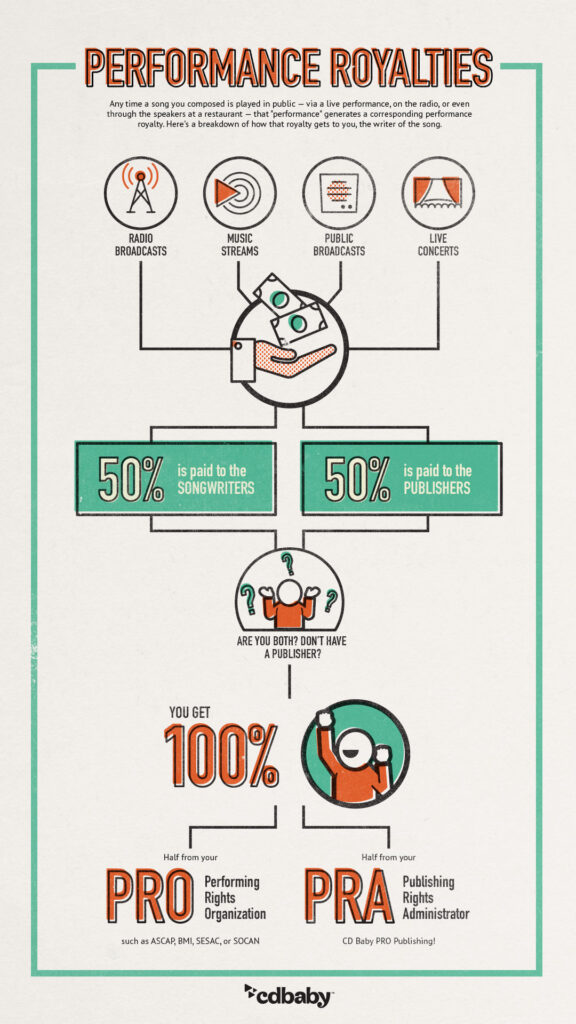

Performance Royalties are generated through copyrighted songs being performed, played or streamed in public and can be divided into two parts: the royalties paid out by streaming services and royalties generated by more conventional public broadcasters — radio, TV channels, venues, clubs, restaurants, and everything in between.

Who Gets Performance Royalties

Performance royalties are paid to songwriters on the composition side of song ownership. Performance royalty are then split 50/50 into two sub royalties: Songwriting and Publishing. Songwriter Royalties will always be paid out to the credited songwriters of the composition (lyrics/music). Publishing royalties makes up the other 50% of the performance royalty and are assigned to outside entities called publishing companies.

If you are not signed to a publishing deal with a publishing company, you might be missing out on 50% of your performance royalties! To avoid this, you must register with a Performing Rights Organization or simply PROs: ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC in the US, PRS in the UK (each country has there own PROs) as a publishing company and a writer to collect both of these royalties or enlist the services of a Publishing Administration Company who will manage, collect and distribute your publishing royalties on your behalf.

Public Performance and Broadcasting Licenses

Broadcasters are required to get a blanket license from their local PRO, giving them the right to publicly perform almost all music in the world. Then, the users will report the music they’ve broadcasted to PROs, which will then use that data to distribute the blanket license money to the corresponding songwriters. Touring performing artists also report their setlists to venues. The venue will then “forward” the setlist to the PRO, and the PRO will allocate the public performance royalties back to songwriters. The same is true for TV channels, venues, clubs, restaurants, and all other establishments that plays music publicly.

Digital Public Performance Royalties

With the rise of the digital stream it gave birth to a couple new royalty stream. Digital streams are unique in that they generate both mechanical and public performance royalties. These performance royalties are tightly linked to the mechanical royalties that the streaming services pay out, creating a so-called “all-in royalty pool”. All-in royalty pool is set by the CRB (Copyright Royalty Board) and it establishes the sum that a given streaming service has to pay out to songwriters and publishers in both mechanical and public performance royalties. The streaming service will pass the public performance portion of the all-in royalty pool down to PROs, which will then allocate it to songwriters and their publishers. Much like the streaming royalties on the master side, public performance royalties are distributed on a per-rata basis

Neighbouring Rights (and Royalties)

Remember, there are two types of copyright in music, one for the composition and one for the sound recording. Neighboring rights are very similar to Public Performance royalties paid to songwriters, except that neighbouring royalties are paid out to the master recording copyright holders for the public performance of their compositions. So, from a legislative perspective, they sit next to performance rights — hence the term “neighboring rights”. In any case, just like performance rights, neighboring rights are collected by PROs in their respective markets eligible for neighbouring royalties collection, and then distributed to sound recording owners. (key word “eligible”)

The US doesn’t compensate sound recording owners “neighboring rights” but airplay in other countries does generate neighbouring royalties. The US rule of not having to pay sound recording owners for radio airplay applies ONLY to AM/FM terrestrial radio. That means that digital internet radio, satellite radio stations and cable radio DO pay the master owners. That means that the digital performance royalties can be considered neighbouring rights payments — but since the use is very specific, it’s easier to use a separate term and keep up the idea that the US doesn’t recognize neighbouring rights.

For the purposes of digital performance royalties collection, the US government has established a designated collection society: SoundExchange. Digital radio platforms must get a statutory license from SoundExchange to use licensed music, and recording artists, labels, and session musicians must register with SoundExchange to collect digital performance royalties. SoundExchange allocates royalties to rights holders based on how often each song was played, with the following breakdown:

- 45% to featured artists

- 5% to non-featured artists

- 50% to the rights owner of the master recording